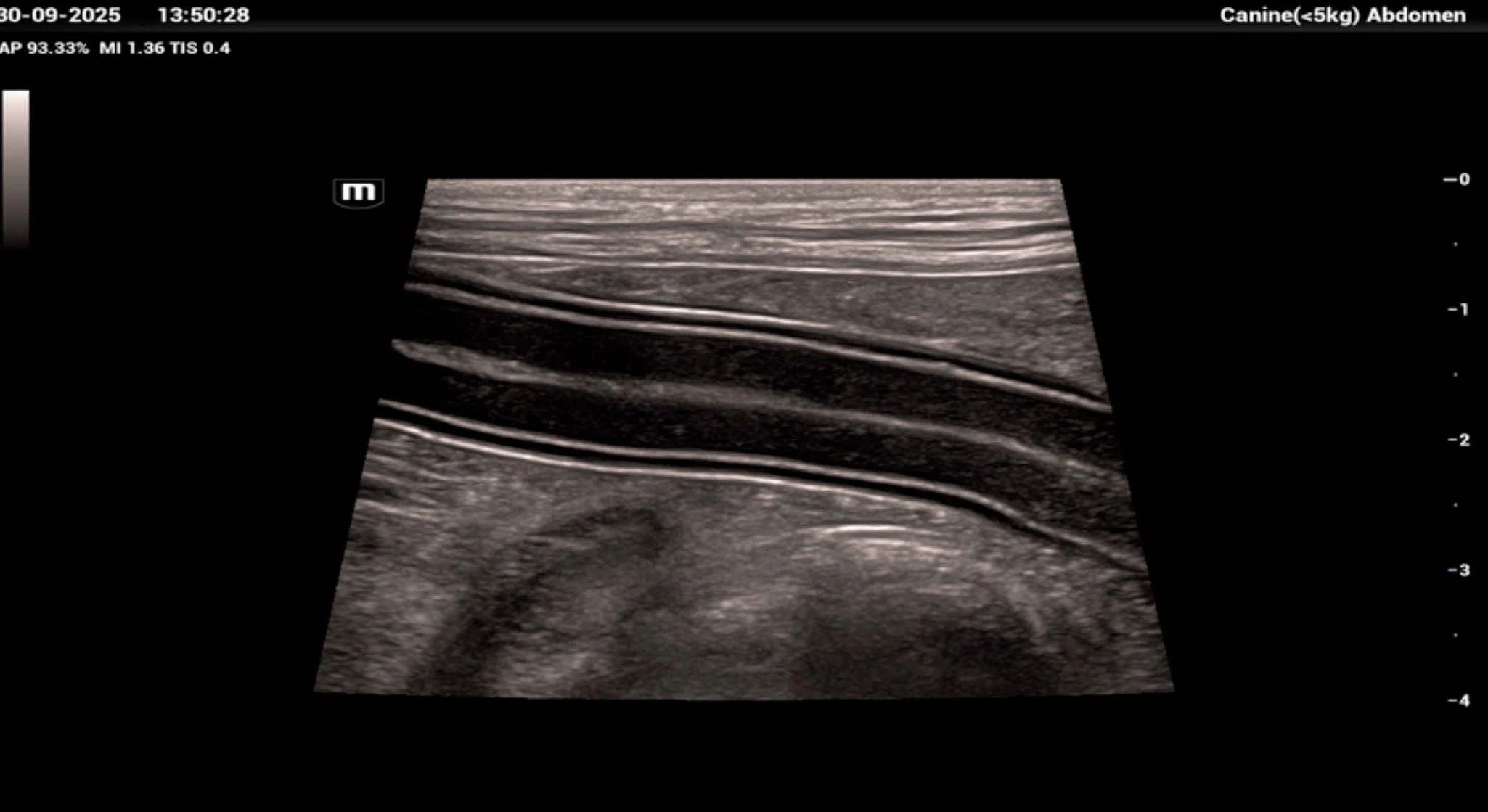

High-resolution ultrasonographic image of canine jejunum demonstrating all five histological layers: mucosal interface, mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and serosa. The clarity of stratification supports normal architecture and provides a baseline for comparison in cases of enteritis, lymphangiectasia, or neoplasia.